Last week I wrote a post about Public Drinking Water Supply and the Loudoun Transition Area, but this time, I want to drill down into a specific development proposal that would impact water quality: the True North Data center application. This rezoning, just upstream of the Goose Creek reservoir, would place a highly impervious use in the same subwatershed as the public water intake.

There is a site plan application on file, which provides the opportunity to look closely at the specifics of the proposal. In so doing, I think there’s an incredibly strong case to make that the existing zoning (TR-10, which means 1 unit per 10 acres) is more protective of water quality than a conversion to office park, as requested.

–Download the True North Data’s Phase 1 Site Plan (85.2MB)

–Read my November 2017 email alert with an introduction to the True North Data issue.

Why do I think it’s worse for water quality than current zoning?

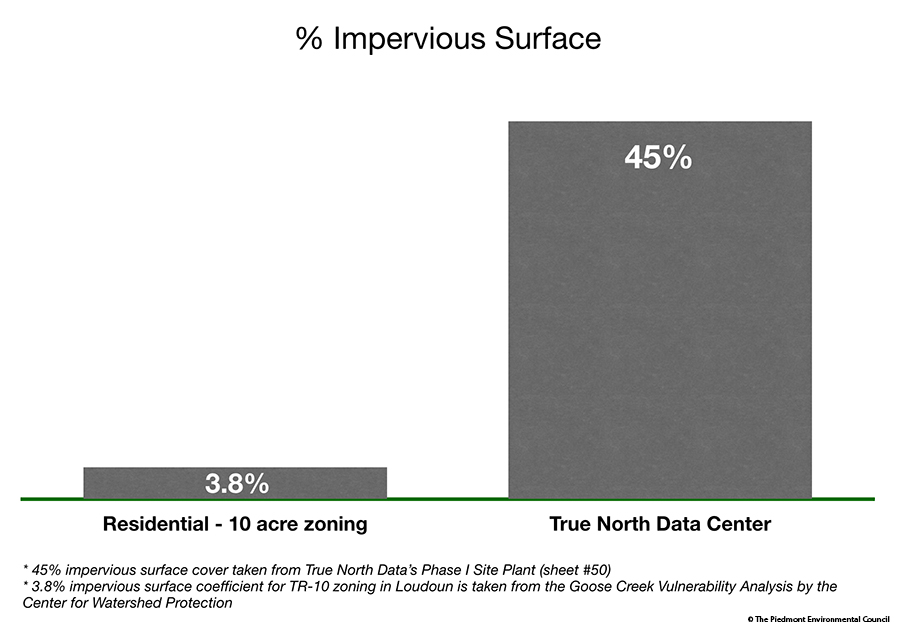

The data center would have a much higher percentage of imperviousness than TR-10 zoning.

Despite assertions to the contrary, a look at the Phase 1 Site Plan submitted by the applicant, shows that impervious surfaces would cover 45% of that portion of the site. Phase 1 takes up just under half of the property, which means there would be ~20 acres of impervious surface for that Phase alone (sheet #50). They haven’t provided the numbers for Phase 2 yet.

By comparison, under TR-10 zoning, the expected impervious cover for the entire property would be around 3.8%, covering ~4 acres.

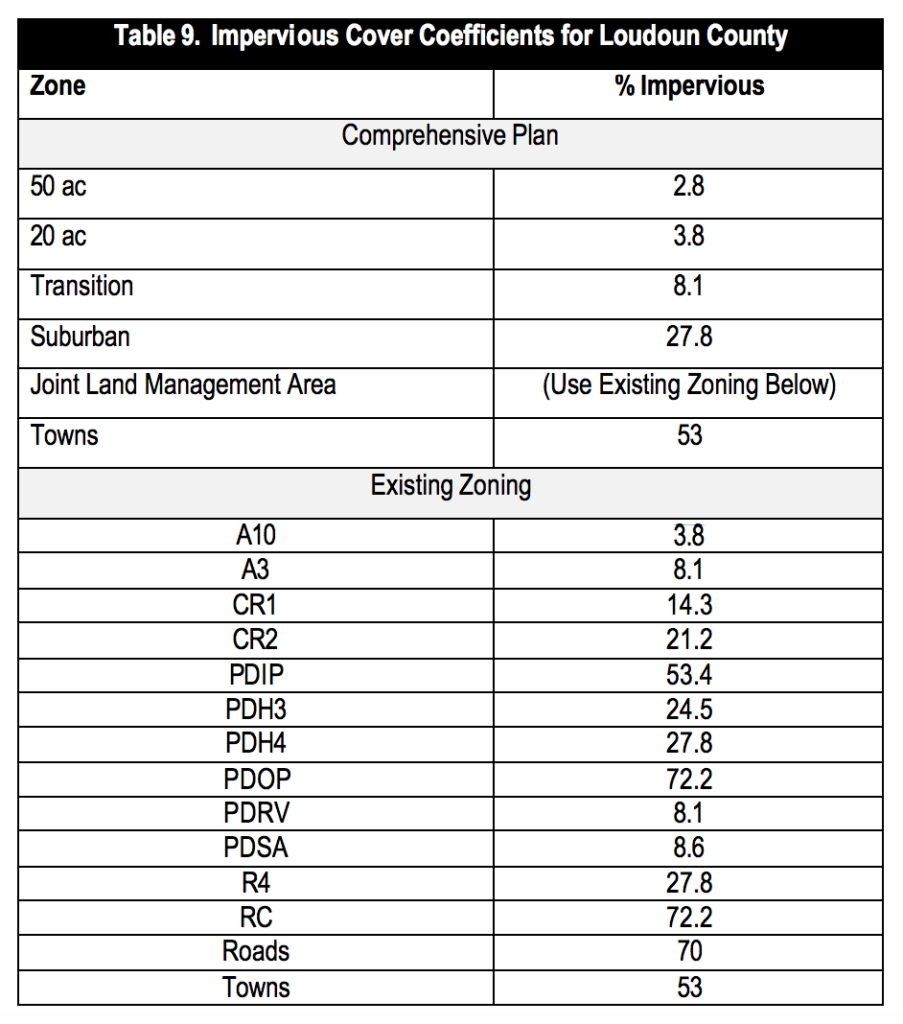

The impervious surface coefficient for TR-10 zoning in Loudoun is 3.8 (which equates to 3.8%). Data source: Page 20 of the Goose Creek Vulnerability Analysis by the Center for Watershed Protection.

Managed turf, only slightly better than impervious surface with regard to its ability to absorb and filter stormwater runoff, would cover 35% of the Phase 1 site plan space. This leaves only 20% undisturbed forest cover, representing a drastic reduction to the site’s natural ability to protect Goose Creek, our drinking water supply.

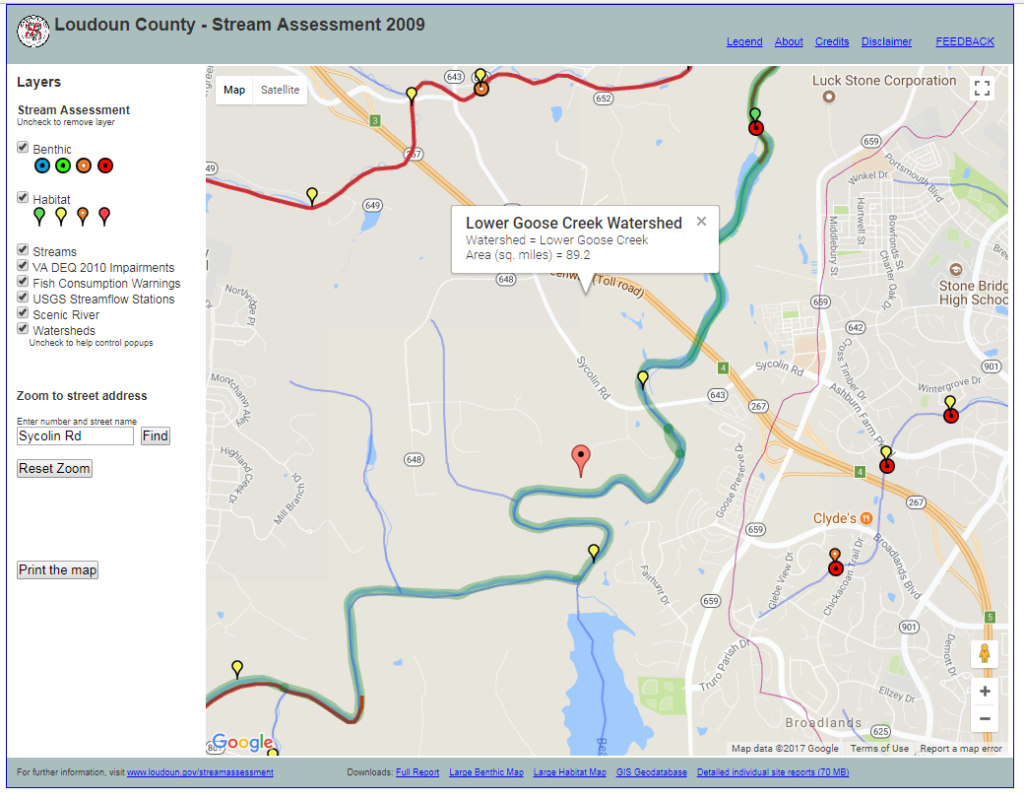

While the segment of Goose Creek near the site is not listed as impaired, the habitat is “suboptimal,” and just over a mile downstream of the reservoir, the stream is not supporting benthic aquatic life (aquatic organisms that live on, in or near the bottom of the stream).

Scores of studies, like this one from the Center for Watershed Protection, have demonstrated a negative correlation between the amount of impervious surface in a watershed and overall water quality. Loudoun has appropriately planned this public drinking water watershed in the Transition Area for low levels of development to offset the higher levels on the Suburban Area side of Goose Creek. The Transition Area side should be protected from development that greatly increases the amount of impervious surface.

Even when applying the worst case, the pursuit of current zoning would result in much less impervious surface than the True North data center proposal.

You can use the County’s online stream assessment tool to see stream health data for stream segments in any area of the county.

The required Best Management Practices (BMPs) aren’t a substitute for the benefits of open land, forests and natural vegetation.

State stormwater guidelines require the use of Best Management Practices to help offset the impacts of the development. However, BMPs have varying levels of pollutant removal and do not fully offset the negative impacts of increased imperviousness. While the applicant has proffered to monitor the stream to ensure that the BMPs are working as expected, this doesn’t make them more effective. The site plan describes two different types of BMPs that are proffered to be used (sheet #50):

Two types of bioretention using plants with an underdrain to slow stormwater and help filter out pollutants.

- These provide a 40% and 80% runoff reduction credit;

- They have a 25% and 50% phosphorus removal efficiencies respectively

- Two types of manufactured filtration products to hold, slow down and reduce the amount of pollutants in the stormwater.

- Neither get a runoff reduction credit;

- They have 40% and 50% phosphorus removal efficiencies respectively It’s worth noting, the efficiencies listed above are only for the small storms that happen most frequently, every year or so.

In a section entitled, SWM & Adequate Outfall Narrative (sheet #43), the document describes how the drainage of the site is being altered. Grading for the development will direct more runoff to the natural stream onsite. It notes that the stream does not show signs of flooding in the current conditions. The authors appear to presume that the stream can handle the extra flow without damage (erosion) because the runoff would flow through the BMPs, which would slow down the flow to a permissible level, even with a 10-year storm. However, I would posit that the flow from bigger storms could start an erosive and damaging process in the stream channel. The recent proffer addition to monitor BMP effectiveness is immaterial in its benefit. It only alerts us to a failing system. The required BMPs are not designed to handle larger storms. They lose efficiency and effectiveness under those conditions, as the stormwater overwhelms their capacity to slow velocity and filter out pollutants. Storms of greater magnitude, i.e. so-called 100-year storms happen more often than the frequency implied in their name. As many learned while following the flooding during Hurricane Harvey this year, the phrase actually means that there is a 1 in 100 chance that such a storm will occur in any given year. In addition, there is a concern that big storms are happening with much greater frequency and severity as the climate changes. Northern Virginia even experienced a 1000-year storm in 2011.

Diesel fuel storage tanks and generators classified as “hot spots” would be onsite (sheet #49).

This additional threat would be much less likely on a residential property. With a spill or rupture, the close proximity to the reservoir and short travel time to the intake would jeopardize defensive measures to close off the intake valves.

It would set the stage for other office/industrial uses in the area.

The push to find data center sites in Loudoun is strong and opening up this part of the Transition Area provides new opportunities at lower cost. An approval here would signal that the area is appropriate and other applications for similar uses could quickly follow suit. The True North Data site is the most sensitive location in this watershed. An approval here would signal that environmental concerns will be overlooked.

In conclusion, the proposed True North Data center would not be as protective of drinking water quality as keeping the existing zoning. This summary from an EPA document entitled “Protecting Healthy Watersheds” sums it up nicely.

Protecting Healthy Watersheds:

- Lowers drinking water treatment costs

- Avoids expensive restoration activities

- Sustains revenue-generating recreational and tourism opportunities

- Minimizes vulnerability and damage from natural disasters

- Provides critical ecosystem services at a fraction of the cost for engineered services

- Increases property value premiums

- Supports millions of jobs nationwide

- Ensures we leave a foundation for a vibrant economy for generations to come

In other words, planning to protect healthy and sensitive watersheds has many co-benefits. It tips the scales in favor of keeping the existing zoning for this property and the Transition Area broadly.

Gem Bingol

Loudoun Field Representative

The Piedmont Environmental Council

More details:

– True North Data Center – Wrong Direction for Loudoun County

– Public Water Supply Protection & the Loudoun Transition Area