Virginia’s northern Piedmont is a beautiful and vibrant place—boasting of forests, rivers, mountains, farmland, thriving towns, and numerous historic and cultural resources. But all of this came under threat in November 1993, when the The Walt Disney Company made a surprise announcement that they planned to build an American history theme park near what was then the small town of Haymarket, VA—only four miles from Manassas Battlefield.

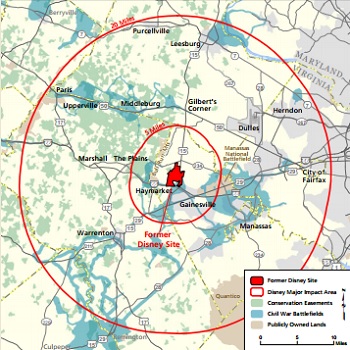

And Disney wasn’t going to stop at a theme park. Prior to their public announcement in November, the corporation had used triple-blind negotiations to quietly take land options on 3,000 acres of rolling farmland. Their plan was to build an urban complex in Prince William County, complete with a theme park, golf course, up to 4,500 housing units, and over two million square feet of commercial space—a massive real estate development in one of America’s most scenic and historic landscapes. And this sprawl wouldn’t be limited to the original 3,000 acres. Analyses were showing that after a Disney park came to town, the surrounding region could expect at least a 20-mile radius of collateral development—as seen in Orlando, FL and Anaheim, CA.

The sprawl of motels, strip malls and restaurants from “Disney’s America” would not only have put serious strains on the Piedmont’s natural resources from increased pollution, but this history-themed park would have put real historic sites at risk. Disney’s chosen location was surrounded by numerous historic towns, dozens of battlefields, and even more historic districts. They wanted to build Civil War rides only four miles from the real Manassas battlefield—where approximately 30,000 men went missing, were injured, or died in battle.

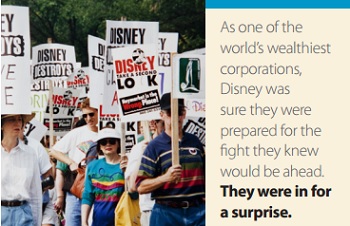

As one of the world’s wealthiest corporations and most influential P.R. machines, Disney was sure they were prepared for the fight they knew would be ahead of them. They were in for a surprise.

Rallying the Troops

Due to the promise of new jobs and significant economic development, many local businesses and politicians initially welcomed Disney’s plan. A regional poll taken the week after Disney’s announcement in November ‘93 showed a 98% recognition of the Disney corporation, 75% of which were supportive of the “Disney’s America” project.

PEC was a much smaller organization at the time, with only seven full-time staff. After Disney’s rollout of its massive plans, PEC was unsure if it should—or even could—get involved. The site was in Prince William, just outside of our nine-county region, and it would be an expensive fight for such a small organization. But, many of PEC’s supporters were turning to staff and board members with questions and requests for help.

So, PEC organized a public meeting to discuss concerns about “Disney’s America” at Grace Episcopal Church in The Plains, VA. It was a cold night and the church was packed—people sat on the floor and filled the choir loft. PEC’s President Chris Miller was 28-year-old environmental lawyer at the time, and he attended the meeting with his cousin. “I was surprised to see so many motivated people in that church,” he remembers. “There was a real, tangible energy.” This meeting galvanized the community, and it was decided that they had to fight Disney’s plan for the future of their home.

‘The Third Battle of Manassas’

The grassroots opposition quickly gained momentum, and citizens were joined by a number of local, regional and national organizations who wanted to stop Disney—including the National Trust for Historic Preservation and the Northern Virginia Environmental Network. A third influential organization called Protect Historic America was formed specifically for this fight. This group of luminary historians and preservationists—organized by Nick Kotz, Mary Lynn Kotz and Julian Scheer—included James MacPherson, David McCullough and Shelby Foote. Protect Historic America focused on the potential impact on the nearby historic sites, as well as the perception of American history.

Miller left his job at a top law firm in DC for a contract position at PEC, where he was tasked with forming a formal coalition from the group of concerned environmentalists, noted historians, citizens, and organizations. This coalition—known as “Disney, Take a Second Look”—launched a multifaceted campaign that involved multiple studies looking Disney’s economic claims and potential alternative sites; numerous press events to garner national attention; lobbying in Richmond; and a number of public rallies and protests. Who could forget the foam-head caricatures of Disney characters that showed up at multiple events, including the opening of “The Lion King” movie at D.C.’s Uptown Theater?

The heart of the campaign, however, came from the thousands of hours spent researching proffers and the fiscal, environmental, and traffic impacts—research which was shared with local and state government officials to help them make better-informed decisions. The coalition cited over 40 alternative locations in the D.C. area that were better suited for such development—due to existing transportation and mass transit infrastructure, as well as needed distance from priceless historical resources. They also revealed a number of holes in Disney’s claims of economic gain for the region. The corporation said that “Disney’s America” would be open 365 days a year—generating $38 million in state taxes and over 12,000 jobs by 2007. Yet, PEC and its partners showed that, due Northern Virginia’s climate, the park could not possibly stay open year-round. Thus, they proved that the project would likely produce no more than 6,000 jobs by 2007—a vast majority of which would be for seasonal, minimum-wage work. And, since the region was largely rural (Haymarket’s population at the time was under 500), Disney would have to bring in the workforce needed from elsewhere. Lastly, the coalition pointed out that it was likely the park would become a net drain on Prince William County’s tax base due to the costs of the infrastructure and services needed to support the resulting development.

Thanks to widespread national media coverage and the coalition’s damning reports, public opinion was changing swiftly. Only a couple of months after the initial poll showing a 75% approval rat-ing for “Disney’s America,” a new poll showed that public approval had dropped to 50%. A few months later, a third poll showed that the tables had turned completely— with 75% of people opposed to Disney’s plans and only 25% approving. It was clear that Disney had underestimated the strength of the grassroots opposition they were facing.

On September 17, 1994 thousands of people came together for a march on Washington—protesting “Disney’s America.” This just may have been the straw that broke the camel’s back, because soon after Disney announced that it was abandoning its proposed park in Haymarket—only nine months after making their plan public.

“The fight with Disney had a profound effect on people’s perception of what the average person could do when faced with a huge challenge,” Miller says. “It changed what people thought was possible for Virginia’s future. Up to that point, many thought that the urban sprawl spilling out of D.C. was unstoppable, but PEC and all of our partners proved that wasn’t the case.”

Twenty years have passed since the grassroots opposition successfully kept Disney out of the Piedmont. Because of this fight, land conservation and land use planning have become important issues in the public consciousness, and this region remains a beautiful, healthy place to live. In fact, since 1994, Virginians have protected an amount of privately-owned land that is bigger than the entire Shenandoah National Park.

Yet, some people look at Haymarket today—which has given way to some major development—and ask, “Are we really better off without Disney?” Follow the link and go to page 8 to read what PEC’s President, Chris Miller, has to say on that subject.

This article was featured in our Fall 2013 Member Newsletter, The Piedmont View.