Restoring Rivers & Connecting Habitat

Rivers naturally flow from the mountains to the sea. Dams and other barriers like culverts can disrupt natural stream flow, disconnect fish and wildlife habitat and impair water quality. Removing unnatural barriers and disruptions is particularly important for conserving our waterways.

“I have seen hundreds of miles of streams disconnected by these barriers throughout the Rappahannock River watershed. The big picture, ecologically speaking, is to reconnect as many miles of stream as we can, so that fish can spawn and swim upstream to find new habitat,” says Celia Vuocolo, our wildlife habitat specialist.

Celia’s work on a PEC survey conducted in 2014 of aquatic passage and barriers has directed recent efforts to restore rivers and streams throughout Virginia’s Piedmont. This survey, directed by our former habitat manager, James Barnes, identified over 133 sites where barriers exist on public and private roads and driveways.

PEC has taken on the work of restoring local rivers by removing culverts and low-water crossings that can be roadblocks to stream health. By replacing these barriers on roads and driveways with fish- friendly designs, we are improving habitat and water quality.

Many aquatic species, including Virginia’s state fish, the Eastern brook trout, benefit from these restoration projects. Ideally, we hope these projects will influence government agencies to incorporate fish-friendly designs as they update roads and stream crossings.

“Most of these culverts were put in during the early 1900s,” says Peter Hujik, our Orange and Madison County field representative and project lead on the stream restoration efforts in Madison. “Many are beginning to fail and will need to be replaced within the next five or ten years, so our initiative is timely.”

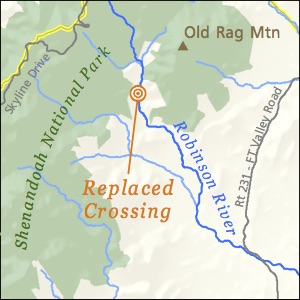

While everyone loves seeing native trout thriving in our headwater streams, the downstream effects on water quality are impressive, too. At Robinson River, 350 linear feet of stream were restored to its natural channel, stabilizing banks from erosion, and ultimately removing sediment from going downstream to the Chesapeake Bay. In all, 5.3 miles of aquatic habitat were restored.

| Robinson River: Before | Robinson River: After |

|  |

When water stagnates behind barriers, sediment can build up and water quality can be impaired. Downstream water can become warmer, causing limited oxygen for fish to breathe. You can tell a stream’s health by the type and quantity of bugs that you find. Where there is poor water quality, you will find less diversity and less food source for fish and other wildlife.

“The project was a total success and the stream through this property has never looked better,” says Karl Beier, landowner along the Robinson River. “The result of this restoration project is both functional and visually impressive. I really appreciate the effort that PEC went through to see this project through.”

Recent work at Sprucepine Branch reconnected 2 miles of stream habitat, as a set of culverts were removed from a private driveway and replaced with a bridge. Both projects at Sprucepine Branch and Robinson River included natural channel design and construction, which was completed by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and Shenandoah Streamworks. The work included regrading stream banks and in-stream structures that restored the natural hydrology of those streams. This stabilizes the banks, as well as improves water quality and habitat, too.

“We are delighted with the changes that the culvert project accomplished,” says Minna Vogel, another landowner along Robinson River benefiting from the effort. “We are so appreciative of all the work and the funding that went into this project, and the very obvious results that we see everyday.”

PEC is thankful for our projects’ supporters, who have given their time, talent and funds toward restoring the Piedmont’s rivers and streams. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service has provided technical assistance and funding for both Sprucepine and Robinson River. The Virginia Department of Game and Inland Fisheries has provided fish population monitoring on both projects, as well. These projects were also made possible because of our partners: the Nimick Forbesway Foundation, Trout Unlimited and the Krebser Fund for Rappahannock County. In addition, we extend our gratitude to the landowners — the Beier, Griffin, Hennaman, Northup, Sutton and Vogel families — who have guided much of our work and contributed financially to its success.

“Because of the complexity and cost of these projects, we are grateful for the landowners, funders and partner organizations who banded together to get the job done,” says Peter.

| Sprucepine Branch: Before | Sprucepine Branch: After |

|  |

We are lining up additional culvert removal projects with our partners for the next several years. Efforts that are currently in the works are located on Kinsey Run near Graves Mill, Bolton Branch near Huntly and Cedar Run at the White Oak Canyon trail head in Shenandoah National Park. Stay tuned for updates on these projects in 2018!

This article was featured in our Fall 2017 Member Newsletter, The Piedmont View.