The rolling hills dotted with patches of forest and large tracts of grazing land off John Tucker Road in Madison County is a beautiful pastoral image. The landscape is largely unchanged in the last one hundred years and one might easily think that this area had always been large tracts of woodland or farmland. However, the presence of an African American cemetery here is uncovering a largely forgotten history that will change the way we think about the African American legacy in Madison County.

In 1850, Madison County’s population was 9,331 inhabitants with 50.6 percent enslaved. There were 151 free Black people tabulated, which made up 1.5 percent of the county’s population. Between 1850 and 1860, the county’s population decreased to 8,854 people, with 4,397 enslaved, demonstrating that half the population was still enslaved. Of the entire African American population of the county in 1860, 98 percent was enslaved, with 97 free Black people counted. A review of the 1860 population census shows only 24 households being free African Americans and of those households; only four were shown to hold their own land. [1]

However, a Black man by the name of Walker Cobler challenged this statistic and the way that we think about Madison County on the eve of the Civil War. He first appeared in the population census for Madison County in 1850. At that time he was living in the household of George and Lucy Racer, who owned a small farm between Great Run (historically known as Grymes Run) and present-day John Tucker Road. In the 1840 census, George and Lucy Racer had a small number of enslaved individuals in their household and it is likely that Walker was previously owned by them. Sometime between 1840 and 1850, Walker Cobler obtained his freedom. In July of 1850, George Racer sold 10 acres of his land to Walker Cobler, and Walker established a homestead there, on a small rise overlooking Great Run. [2]

Despite the odds, and the fact that Virginia officially required free Black people to leave the state after 1806, Walker and a woman named Frances Carpenter (also known as Frances or “Fanny” James) challenged this law and continued to assert their freedom and independence by remaining on their 10 acres of land and raising a family there. Between roughly 1847 and 1861, the couple had six children together, Mary, Priscilla, Laura, Lucy Ann, James and Edward.

Walker Cobler is enumerated in the 1860 agricultural census and through this record we have a unique snapshot to better understand the lives of Walker, Fanny and their young family. They were among the only Black families in Madison County to be enumerated in the 1860 agricultural census. The Cobler farm included six improved, tilled acres and two unimproved acres, which were likely woodland. The cash value of the farm was $100 in 1860. The family-owned one hog and had likely owned numerous other animals, as the census showed that there was $430 in animals slaughtered during the year ending June 1, 1860. The family grew five bushels of peas and beans, 10 bushels of white potatoes, 30 bushels of sweet potatoes, 200 pounds of butter, seven tons of hay, three bushels of clover seed and five bushels of grass seed during the year ending June 1, 1860. Additionally, they produced 12 pounds of flax and 3 bushels of flaxseed, which was likely used to make linens and clothing for the family. The seven tons of hay would have been more than enough for the small herd of animals on the Cobler farm, so it is likely that the family would have sold extra to neighbors. While the family was not shown owning cattle, due to the large quantity of butter produced, it is likely that they had owned at least one head and it was among the animals slaughtered during 1860. The census data paints a picture of a small family farm operation, similar to many other Madison County farmers at that time.

They were among the only Black families in Madison County to be enumerated in the 1860 agricultural census.

By 1870, the Cobler family had taken on the surname of their mother, Fanny James. Some of the older children were adults and established their own families during the decade following the Civil War, with daughters Mary and Priscilla giving birth to several children between 1870 and 1880. On October 1, 1876, Walker Cobler passed away at only 48 years old. It is believed that he was buried in the family cemetery established just to the west of his farmstead.

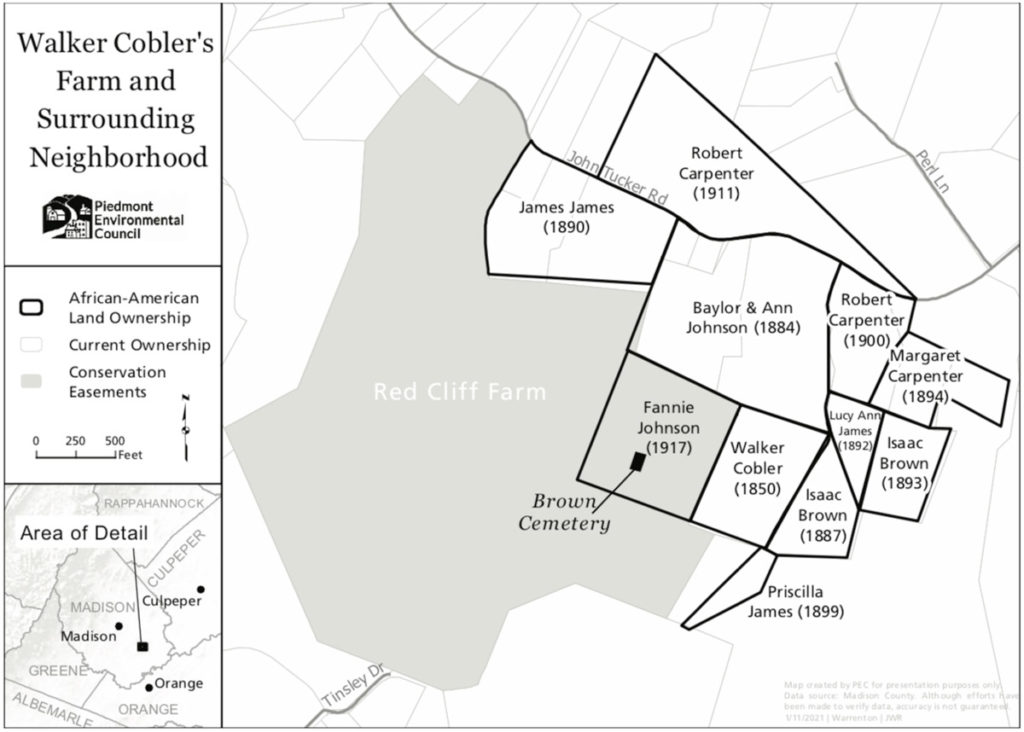

The years following Walker’s death must have been trying for the family, but they undoubtedly leaned on their neighbors that lived nearby. The community around the Cobler-James farm grew rapidly in the decades after emancipation. Ann Johnson, wife of John Baylor Johnson, purchased 30 acres of land from James and Ida Reddish in 1884. Baylor and Ann settled on the northern end of the 30 acre property, which was ultimately divided, with their son, Henry, and his wife, Fannie, taking the southern portion. Several of the James children acquired land of their own near or adjacent to the Cobler/James homeplace. Isaac Brown, who had married Walker and Fanny’s daughter, Laura, in 1882, purchased nine acres from James and Ida Reddish in 1887, which was located just east of the homeplace. James “Jim” James, son of Walker and Fanny, purchased 20 acres from the Reddishes in the spring of 1890, northwest of the Johnson lands. Lucy, daughter of Walker and Fanny, purchased six acres adjacent to the homeplace and sister Laura’s land, from the Reddishes in 1892. Daughter Sillah purchased two acres from Robert Reddish and wife in 1899. Margaret Carpenter, who had likely been enslaved alongside Walker Cobler by the Racers, also acquired land nearby. She purchased six acres from Blanche and W.P. Yowell in 1894, and had acquired additional adjacent acreage prior to that date.

The beginning of the Twentieth Century in Madison County was a time of increasing self-determination and agency for African Americans as is evidenced through land ownership. Although only 36 percent of farmers in Madison County in 1910 were Black, 95 percent of all Black-operated farms were owner-operated, in contrast to only 86 percent of white-operated farms. The trend towards owner-operated farms amongst the African American population in Madison County was significantly higher than the 67 percent seen statewide. [3]

Evidence of this trend is apparent in the small community off John Tucker Road as well. Two of Margaret Carpenter’s children, Elliott Carpenter and Zora Carpenter, married and remained in the community. Elliott Carpenter married Mary Baker in 1895, daughter of Benjamin and Ella Baker, and purchased Jim James’ land off John Tucker Road. Jim James continued to live on the property and Elliott and Mary constructed their own home to the east of his and farmed the land. Zora Carpenter married Hamp Reid in 1894. Zora and Hamp moved from Washington, D.C. back to Zora’s home place after her mother’s death. She purchased the interest from her siblings in her mother’s land in 1910. Margaret’s daughter, Ida, had a son, Robert Lewis “Bob” Carpenter, in 1878. He operated his farm and raised his family on a purchased piece of land his grandmother had acquired decades prior.

By 1910, this area off John Tucker Road would have been a lively, bustling place with at least nine families (one of them being a white family renting land in the community) and roughly 40 people residing here. Almost all of the families owned small plots of land that they farmed to provide for their immediate families. The 1910 the census also shows the beginnings of a diversification in employment and a shift from farming as a primary occupation to service industry positions. For example, Robert Lewis Carpenter worked as a teamster for a saw mill, meaning he was responsible for loading wagons with lumber to be taken to a local mill for processing. John Baylor Johnson’s niece, Lizzie Jackson, who lived with him and his wife in 1910, found employment as a private cook. Priscilla James served as a laundress for a local family. By 1915, every African American household living in this tight-knit community owned the land on which they lived.

In the fall of 1918, the Spanish Flu reached Virginia, hitting Camp Lee at Petersburg and quickly spread from there. From death certificates, we can see that the epidemic was raging across Madison County by the holiday season of 1918. On January 13, 1919, Georgia Carpenter, an 11 year old daughter of Elliott and Mary Carpenter, was the first to succumb to the flu in the community. Four days later, Jim James died on January 17. Three days later Isaac Brown died. Isaac’s wife, Laura (James) Brown followed on January 25. Although no death records can be located for Isaac and Laura’s two children, it is believed that they succumbed to the flu as well. [4] In twelve days’ time, this community buried between 10 and 15 percent of its residents in the same cemetery where Walker Cobler had been buried decades prior.

In the years following the Spanish Flu, much of this land remained in the ownership of some of the same, original families, but the population of the community decreased dramatically in size. Baylor and Anne Johnson’s son, John B Johnson, sold the land he inherited from his parents to Robert Lewis “Bob” Carpenter, who purchased several parcels. Zora Carpenter Reid and her husband, Hamp, acquired some of Isaac and Laura Brown’s estate, when their property went into chancery following their deaths, including the Walker Cobler home place. They lived there until Hamp Reid’s death in 1935. Raymond Nelson, their nephew, acquired the property in 1940 and it remains in the hands of the Nelson heirs today. Elliott Carpenter and his family remained on their property on John Tucker Road until Elliott’s death in 1972. Robert Lewis Carpenter, Jr., the son of “Bob” Carpenter, eventually acquired nearly 130 acres here, which he owned until his death in 2001. [5]

Today there are only a handful of reminders of this once thriving community, the most important being the community cemetery. Standing on a knoll amongst black walnut trees overlooking the Mahanes Farm to the west and Great Run to the south, the cemetery has numerous uninscribed fieldstones. Two engraved headstones mark the burials of Isaac Brown and his wife, Laura James Brown. The cemetery is laid out in roughly three long rows with burials oriented in the east-west direction. A visual assessment of the cemetery indicates that there are roughly 25 marked burials but likely upwards of 50 burials due to the number of unmarked depressions. Based on death records information, the cemetery was likely active from the mid-1870s, with the death of Walker Cobler in 1876, until the 1930s. It is believed that most of Cobler-James, Baylor and Ann Johnson, and Carpenter families are buried here.

Recognizing these unique histories and preserving these important places are a crucial part of telling the full American story.

The cemetery is owned today by Judy Mahanes, part of a larger 168-acre farm, which has been in her family since the 1890s. Her farm includes part of the land originally owned by the Baylor and Ann Johnson family, which remained in the Johnson family into the 1950s. In 2013, Judy placed her farm into a conservation easement, held by The Piedmont Environmental Council, which will permanently protect the land and includes a special provision protecting the cemetery and its funerary markers.

Judy’s commitment to protecting her farm and the cemetery on it is an important step in identifying, documenting and preserving important historic sites across the state, which tell the story of historically under-represented and marginalized communities. The story of Walker Cobler and Margaret Carpenter is an incredible one that deserves more attention, but these tales of remarkable people and their triumph against adversity can be found in communities across the state. Recognizing these unique histories and preserving these important places are a crucial part of telling the full American story.

This article was originally published in Madison Historical Society’s January, 2021 newsletter ‘Preserving Yesterday Enriches Tomorrow’

[1] Statistics derived from 1850 and 1860 US population census results for Madison County.

[2] Walker was not shown as owning real estate in the 1860 census, but George M Racer sold 10 acres of land to him on July 2, 1850 for $100. This deed was recorded in Madison County on September 1, 1851.

[3] Data compiled from the 1910 Census Abstract Supplement for Virginia, accessed at https://www2.census.gov/library/publications/decennial/1910/abstract/supplement-va.pdf.

[4] The 1910 census shows them as living children of Laura Brown and daughter Julia resided in the home with her parents. By 1919, when the estate of Isaac and Laura is in chancery proceedings, there are no immediate living heirs, so it is suspected that both children were deceased at that time.

[5] The chain of title for the Walker Cobler property is incomplete, but the land tax books for 1940 show that Zora Reid, Hamp Reid’s wife, sold the land to George Nelson in 1940.