My home office is in a barn, which means I get to interact daily with the resident barn swallows, Hirundo rustica. Their Latin name means “from the country,” an emblematic moniker that I wish I could stick on the end of my name or title somehow… Swooping, diving, and catching their food in mid-air, they are a wonderful distraction for me to engage in. At dawn and dusk, they are most energized in their mid-air ballet and are nothing less than the most pure delight at twilight. Only once the curtain of night has fallen can I catch my breath and find myself relaxing to the twinkle of the fireflies as they dance out the darkness from the meadows below to the tops of the trees.

It is early summer on the farm, which means the barn swallows have already flown from their winter homes as far south as Guatemala along the southern coasts of the Gulf of Mexico and maintained course for their breeding grounds, which are widely distributed throughout North America. Indeed, the barn swallow is a common species of low conservation concern, but nevertheless is a resilient and elegant bird that captures my imagination… How do they know how to return home to my barn, all the way from Guatemala?

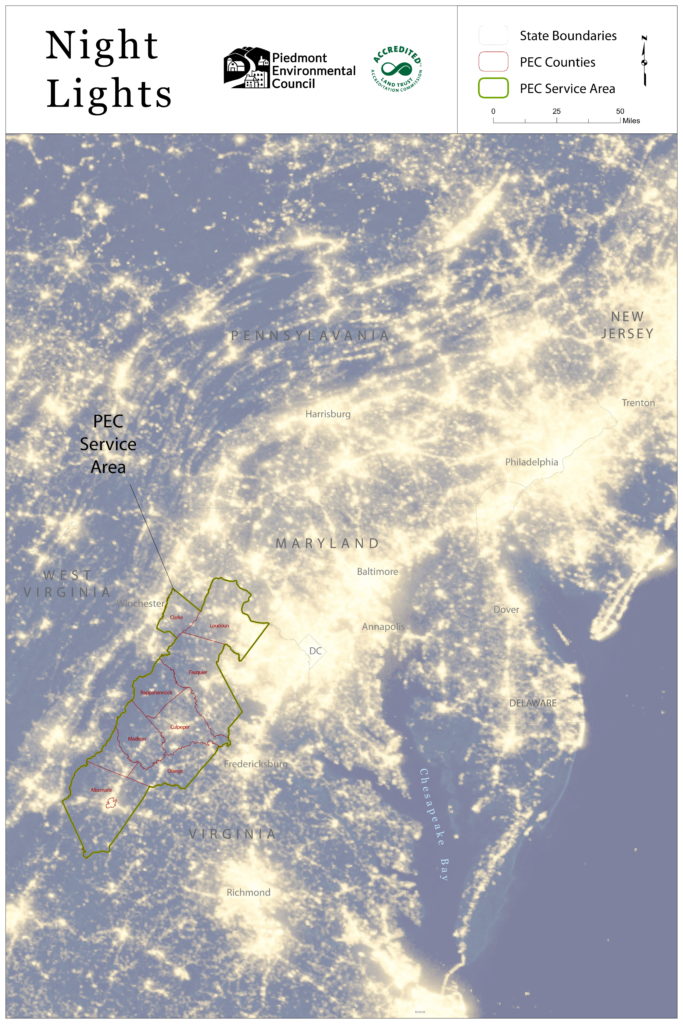

Their intercontinental migration is almost exclusively done at night (as many as 80 percent of migrating birds are inclined to fly in the dark), as night flights hold fewer predators and other distractions from their course. Cities, especially along the Mid-Atlantic coast’s megalopolis, are major problems for migrating bird species, since artificial lights and skyglow can cause confusion at best, collision at worst. The Audubon Society and the International Dark Sky Association have teamed up to tame the urban skies and make them safer for migratory birds. Their Lights Out Programs partner with cities, building managers, and local organizations to minimize excessive lighting, especially during the early spring and late fall migration seasons.

Here in the Piedmont, and especially in Rappahannock County, we are fortunate to have bright stars in the sky at night that are the guides for traveling birds as much as they are the hallmark of a well-protected landscape. With more than 426,657 acres protected from future development with permanent conservation easements, our Piedmont is a refuge for birds and wildlife that seek intact forests, fields, streams and skies to call home.

Local communities have recently come to embrace additional protections for dark skies, with zoning ordinances that set limits for brightness and placement of certain lighting fixtures. The Rappahannock League for Environmental Protection (RLEP) has successfully replaced over 230 lights in Rappahannock County and has also certified our only county park as an International Dark Skies (IDA) “Silver Tier” Park, for its “exceptional and distinguished quality of starry nights and a nocturnal environment that is specifically protected for its scientific, natural, educational, cultural heritage, and/or public enjoyment.” Also along the Blue Ridge in the northern Piedmont is Sky Meadows State Park, a recently designated IDA Dark Skies Park that is ringed by a protected landscape of conservation properties, including PEC’s own Piedmont Memorial Overlook.

Without the solace and safety of a night sky, neither the barn swallow nor I would know that I am home. Sometimes, I am walking through the barn at night to enter the door to my barn office, which is embedded in the empty black space where the birds have nested. I know by a flick of a wing that the swallows have detected me from their overhead mud and grass nests, built like apartments over each barn stall’s electrical outlet. With their shudder of feathers and a brush of cool night air, I know that my swallows have bedded down for the night with their young clutch of a family. I close the door to the barn as silently as possible and bid my aviary goodnight. I find my way to the front door only by the blue-hue of starlight and the yellow moon, commonly known in the country as “nature’s flashlight.”