This article was written for The Piedmont Virginian Summer 2013 Issue.

Tick Season

Adult female deer tick.

Photo by Lennart Tange, CDC

One of the reasons I love my job is that I get to spend a lot of time outside – exploring beautiful properties, walking landowners through the their goals, observing wildlife, and so forth. This time of year though you have to watch for ticks and tick-borne diseases.

In a departure from my normal column on creating habitat, here is some knowledge on ticks ecology and preventative measures from the perspective of an ecologist who spends a lot of time outside. With a little education and forethought, you and your family can better enjoy the outdoors all season long. First – a word of warning: I’m not a health professional by training, so always consult your doctor if you have health concerns.

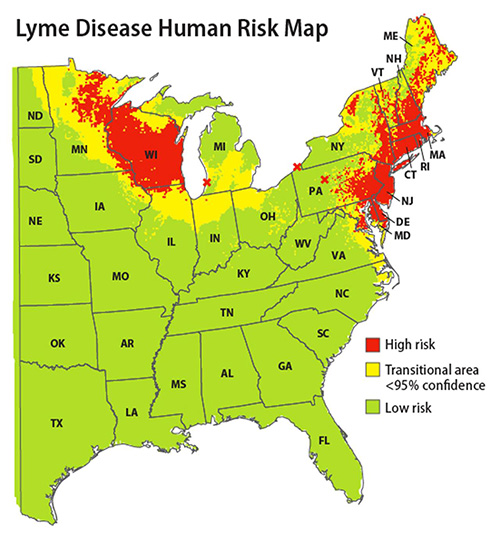

Prior to joining The Piedmont Environmental Council (PEC), I worked in Rhode Island about an hour from Lyme, CT — the town where Lyme disease was first diagnosed. A quick look at the distribution of Lyme disease cases shows that southern New England, along with Wisconsin, is ground zero for the disease. These regions have dealt with Lyme for longer and at a higher prevalence than anywhere else in the country. Anecdotally, all of my co-workers had contracted Lyme disease at least once. I quickly learned tricks to minimize risk, and when I left Rhode Island after two years, I only had four tick bites and no Lyme.

Life History & Ecology

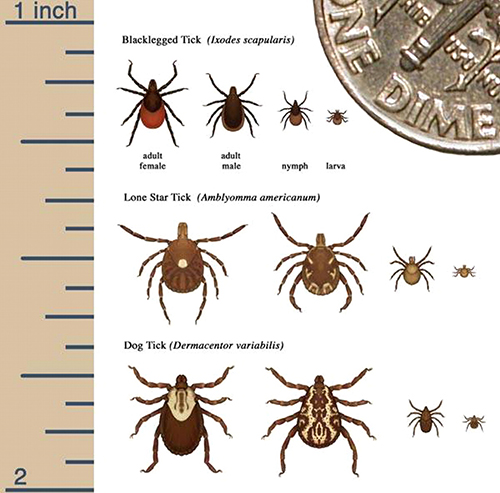

Tick species relative life stage sizes

Photo courtesy CDC

Four common ticks in the Virginia Piedmont include the deer tick (aka black-legged tick; Ixodes scapularis), the lone-star tick (Amblyomma americanum), the dog tick (Dermacentor variabilis), and the brown dog tick (Rhipicephalus sanguineus). I’ll focus on deer ticks since they carry Lyme disease, but there are a lot of similarities.

Ticks have three life stages: larva, nymph, and adult. They need a blood meal at each stage to move to the next form. In the first stage as larvae, ticks are very small and don’t carry Lyme. They change into nymphs in after having their first blood meal. If this blood meal is from an animal that carries a tick-borne disease such Lyme, Babesia protozoa, or Anaplasma bacteria, the tick can then become infected.

Animals that carry these diseases are called reservoir hosts and rodents such as white-footed mice are the main reservoir host for Lyme. According to research in New England, approximately 25% of tick nymphs carry Lyme due to biting an infected host. Contrary to popular belief, however, deer don’t carry Lyme. They are just great transport vehicles for ticks.

So, a tick can potentially infect a human with a disease, like Lyme, starting at the nymph stage. From personal experience, the nymph stage is perhaps the most worrisome since the ticks are so darn small (smaller than the letter “D” on a dime).

Nymphs become adults after their second blood meal. In the adult stage, only female ticks can infect a human with Lyme disease. Male ticks can bite, but don’t feed after the nymph stage. Adult female deer ticks are identified by their brown-ish “pac-man” marking. An adult female is infected if either larva or nymph blood meal was from a Lyme reservoir host (estimated 50% of adults).

In terms of habitat, ticks prefer moist areas with leaves/debris and high humidity like stone walls, brush piles, etc. Anywhere there are lots of deer or rodents is also potential habitat. Interestingly, there is some research that has shown that Japanese barberry — a non-native invasive shrub still in the nursery trade — provides ideal rodent (and hence tick) habitat due to its growth form.

So, don’t buy barberry and ask your local nursery to stock native alternatives!

Ticks do not jump, nor do they drop down from trees. They “quest” from ground level to knee-high. If you’ve ever had a tick bite on your neck or arm, that tick probably started at your shoe and crawled up.

Prevention

Lyme Disease risk

Photo courtesy CDC

So, what can you do? First the good news — most tick-borne diseases (including Lyme) require attachment of 24 hours or greater for transmission. In other words, a quick daily check is enough to prevent Lyme. Beyond this, I always use insect repellant spray when working outside. As of now, there hasn’t been significant scientific testing on natural products like citric acid or citronella for ticks, so that means synthetic repellents like DEET and Permethrin.

While DEET provides some protection, research from Rhode Island has shown that DEET wears off very quickly. That chemical is also applied directly to the skin, which personally makes me a bit uneasy. Instead, I use a 0.5% permethrin spray on my clothing. Permethrin is sprayed directly onto clothing and shoes, not skin, and allowed to dry. Unlike DEET, permethrin lasts for 7 weeks or 6 washings. Since it is a strong chemical, I am very careful with application.

Tick research has shown that boots are by far the most important things to spray with permethrin (74X protection vs. no permethrin) , followed by pants (5X), then shirts (3X). Personally, I have three dedicated permethrin outfits that I wear for outside work and am very conscious about wearing and washing them. You can also buy pre-treated permethrin clothes (or have a company treat your own clothes), which last for 70 washings.

I am generally against spraying for ticks in yards and neighborhoods. In my opinion, a little precaution and common sense on our part is the better choice — not systematic elimination of insects. One alternative are tick-tubes, which you place in mouse habitat around your yard and contain mouse nesting material treated with permethrin. Finally, if you do have a tick bite, always save the tick in plastic bag, in case it needs testing.

The Future

Scientists aren’t exactly sure why Lyme and other tick-borne illness are on the rise — there are probably several causes. However, land use changes rank high in the putative list. As development and sprawl increases, we carve up large, intact forest blocks into smaller pieces (like suburbs) and promote ideal habitat for rodents and deer, the main hosts for lyme. In other words, policies that support land conservation and smart growth aren’t just for the environmentalists, they’re smart for public health as well.

For more information on ticks, James Barnes highly recommends www.tickencounter.org. James Barnes is The Piedmont Environmental Council’s Sustainable Habitat Program Manager. He provides technical assistance to landowners interested in wildlife habitat in the Piedmont. For more information about PEC’s habitat and land conservation work, visit www.pecva.org