For over 400 years, the role of African-Americans has been integral to the story of our nation and their legacy is expressed through the built landscape all around us. Historically overlooked, the stories associated with their struggle for freedom and equality, the stories of African-American entrepreneurship and agency, can be told at historic places throughout Virginia’s Piedmont. For Black History Month, we wanted to focus on some of these important stories and their associated sites, which have been preserved and protected in perpetuity for future generations.

(These stories were originally posted on our Facebook page.)

Gilmore Cabin

One such historic site is the Gilmore Cabin property, a 19-acre portion of James Madison’s Montpelier in Orange County, VA. In 2009, the Piedmont Environmental Council and the Virginia Department of Historic Resources worked with the National Trust for Historic Preservation to protect this special place with a conservation easement.

The property’s most prominent feature is a one and a half story log cabin, where George Gilmore lived with his wife Polly. George, born into slavery at Montpelier, was emancipated at the end of the Civil War. Following the war, he and his wife, Polly, leased the land from Dr. James Madison, building the house by 1873 and eventually purchasing the land and house outright in 1901. Their family cemetery, containing several fieldstone markers, is located near the house and is part of the Gilmore Cabin property as well. By the time the property passed out of the Gilmore family ownership in the 1930s, at least three generations of the Gilmore family had lived there.

Rebecca Gilmore Coleman, who is pictured below, is George’s great-granddaughter. In 2001 she had the family estate restore the cabin.

The property is free and open to the public to visit seven days a week, though the cabin itself is only open some weekends. Parking is available at the cabin on the north side of Route 20. Visit montpelier.org for more information.

Brown/ James Family Cemetery

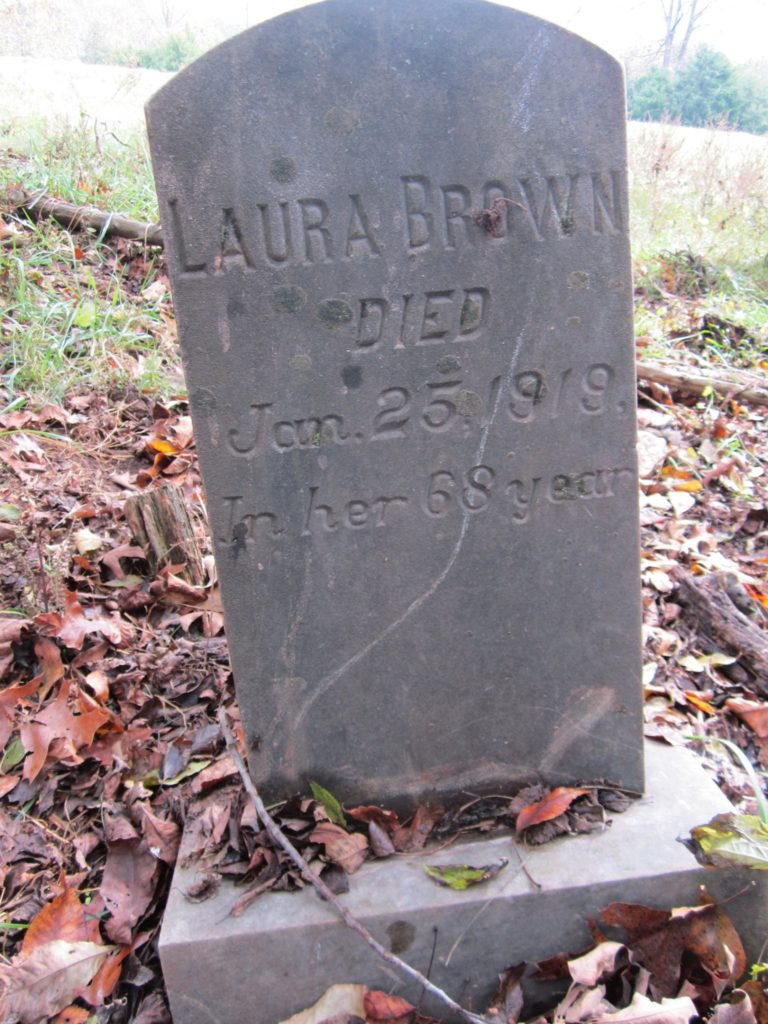

In 2013, the Piedmont Environmental Council worked with a landowner in southeastern Madison County to protect her 168-acre farm, land that had been in her family for generations, with a conservation easement. A portion of her property was historically owned by the Brown/James Family, an African-American family with deep ties to the area, and includes the family’s cemetery, which has been protected by the conservation easement.

The land on which the cemetery stands today was part of an 11-acre tract of land, purchased between 1850 and 1860 by a free African-American named Walker Cobler. In 1860, 99% of Madison County’s African-American population was enslaved, but Walker Cobler, his wife, Frances James, and their children, were part of the 1% that were free. Walker was also one of only a handful of African-Americans to own their own farm at that time. His land was passed down to his children and eventually purchased by his daughter, Laura James and her husband, Isaac Brown. The Browns raised their family here until their untimely deaths from the 1919 Influenza epidemic. Today, the cemetery’s burials include both Laura and Isaac Brown, Laura’s parents Walker Cobler and Frances James, and at least two of Laura’s siblings, Priscilla and James.

Tibbstown

Another important place is the community of Tibbstown, in western Orange County, Virginia, an African-American settlement established by freed slaves shortly after the Civil War.

In 2013, the Piedmont Environmental Council worked with landowners to place an easement on their 159-acre property near the community of Tibbstown. The property includes several family cemeteries and the ruins of a home site associated with the Jones and Parker families, which have deep ties to the Tibbstown community. Both the home site and cemeteries have been protected by the conservation easement.

More about the Jones Family and Tibbstown:

Gilliard Jones, the head of the Jones Family in Virginia, came up to Orange County from North Carolina, in the years following the Civil War. Gilliard was a blacksmith and initially set up a shop in Somerset, which was likely later moved to Tibbstown. Gilliard’s son, Daniel Jones married Julia Fields, and the couple established a home near Gilliard’s, on the slopes of Hardwick Mountain. Daniel and Julia’s son, Prince Jones, also grew up on Hardwick Mountain and served for over 30 years as chairman and deacon of the nearby Blue Run Baptist Church.

The preservation of part of the Tibbstown community through the 2013 conservation easement ensures that we remember the important contributions of the African-Americans of Orange County and their legacy. Today, the current owners of the property, and donors of the easement mentioned above, have lovingly named their property “Prince Mountain,” to honor Prince Jones and his family. (Information shared here credited to Dr. Matthew Reeves, Director of Archaeology at James Madison’s Montpelier)

Orange County African American Historical Society