One unseasonably warm, early spring morning, I walked down Hungry Horse Lane in Rappahannock County with Earl “Kit” Hawkins and his wife, daughter and son-in-law. Eastern bluebirds, a staple in these Appalachian mountains, sang their lovely songs while the Hazel River flowed strong from recent rains. In less than a quarter mile, we turned to follow an old, steep mountain road called Sam’s Ridge Trail. With a quick elevation gain of more than 1,000 feet, this trail in Shenandoah National Park is not for the faint of heart! But we were pushed by a desire to visit what was once the homestead of Kit’s grandfather, Milton “Mortimer” Hawkins, and the place where Kit’s father, Earl Sr., was born and raised.

Long before Shenandoah National Park was established in 1935, generations of people pushed up into the Blue Ridge Mountains and called them home. Houses dotted the hillsides and hollows, churches and schools served the population, and general stores and post offices brought services directly into the mountains. The advent of the automobile and creation of Skyline Drive marked the arrival of gas stations at the top of the mountain, and a few homes even had a telephone and electricity.

Mortimer Hawkins and his wife, Stella B. Nicholson, were among those families who made the mountains home. In fact, both their families lived in the Blue Ridge going back at least to the 1870s. Mortimer’s father purchased the Hazel Mountain land we hoped to find from Calhoun Weakley in 1898, shortly before his own death the same year. Mortimer and Stella married in 1904, moved into the Hawkins house with Mortimer’s mother, Mary, and raised their own family there.

Life on the mountain was not to last, however. By the mid-1920s, the Blue Ridge Mountains were selected as the location for the country’s next national park. Perhaps seeing the sad fate of their mountain community on the horizon, Mortimer and Stella, their children, and Mary, all moved out of the mountain to the Little Washington area, leaving their family home behind. And in the 1930s, the state used eminent domain condemnation to take nearly 200,000 acres of privately owned land in eight counties for the creation of Shenandoah National Park. Thousands of people lost their land, homes, and for many, the only way of life they had ever known.

“Landowners with clear title were compensated, but some families did not possess a title to the land on which they lived. Many were tenants or caretakers for absentee owners, and a few resided on land that had supported their families for generations, but was actually owned by others. Compensation varied from property to property. Some received what they considered fair value for their loss, while many did not,” according to the Blue Ridge Heritage Project website.

Until recently, descendants of these families have been unable to learn much about their families’ experiences in the Blue Ridge. Little public information was available, and boxes of uncategorized records were housed in various locations. But in 2017, James Madison University began digitizing thousands of legal documents related to condemnation of private lands in Rappahannock County for the park.

We saw a unique role for PEC, as part of our ongoing mountain heritage work, to continue the effort in other counties. With the support of Rappahannock County Clerk’s Office, we raised money to buy equipment and hire a contractor, Debbie Keyser, to digitize the condemnation records in Rappahannock County.

Debbie, a former Rappahannock county administrator and a descendant of two displaced families, said, “it has been a privilege to be part of this project. The documents preserved and made available to the Shenandoah National Park descendants allows us to take a step back in time and learn details of our ancestors’ lives. It is a treasure of historical family documentation.”

Missy Sutton, whose ancestors once lived in the Sperryville area of the park, agreed. “As a descendant of William Jackson Rutherford, who was forced to leave his home when his 300 acres were condemned, I find comfort knowing the story of what happened is being shared far and wide via this digital collection. Today, Shenandoah National Park is a tremendous resource and one I enjoy—yet it’s important to remember the sacrifices that had to be made for us to have this resource,” she said.

As we stepped off Sam’s Ridge Trail into the woods that spring morning, we didn’t spot it at first—the Hawkins home. The brush and briars were tangled together in a huge, dense mess just below the trail where the house would have stood. Then suddenly, a ray of sunshine stole through the trees and illuminated an open area that looked rather like an old field. We made a beeline to that spot, and there stood the old stone chimney, just where it had for more than a century, a testament to the skill of the mountain people who built it by hand.

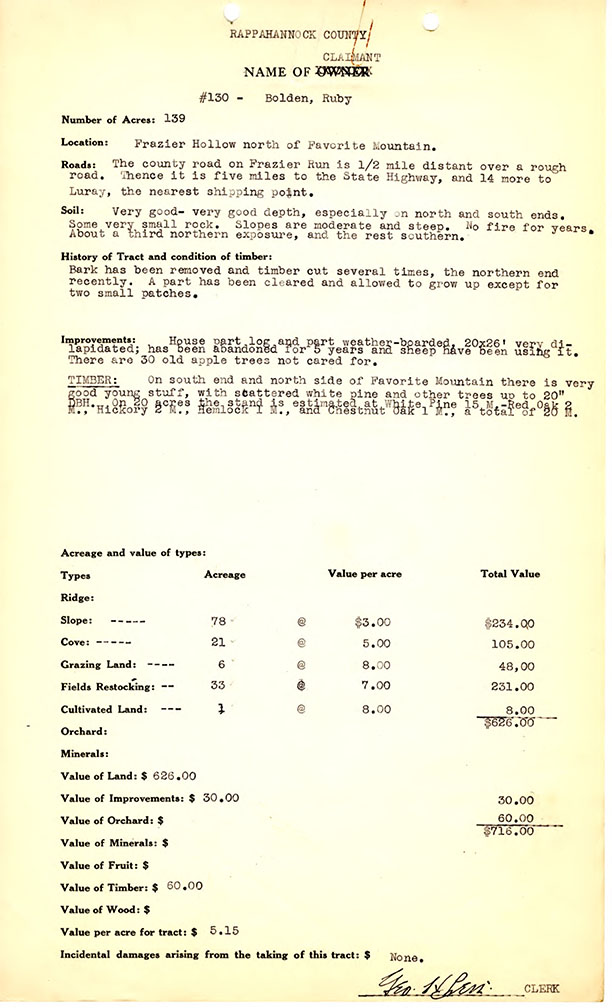

The condemnation records, which include tract assessments, detailed information about improvements, natural resources, title information, and other important details, provide incredible insight into the experience of families that lived in the Blue Ridge. By digitizing, we are not only enabling descendants and historians to access them, we also are permanently memorializing the tremendous sacrifice they made for a park that today provides such incredible access to nature and recreation. The records for Mortimer Hawkins’ property included a survey showing the location of the house near a stream, allowing me to obtain a GPS point with which I was able to navigate through the backcountry and locate the remains of the house to show Kit and his family.

“What an incredible opportunity to connect with the past,” Kit said, reflecting on our visit to his family’s homeplace. “Seeing the chestnut logs that framed the foundation, the stone chimney that was still standing, and the daffodils, black raspberries and the old spring made it seem like home.”

Shenandoah National Park is an incredible natural and cultural area enjoyed by millions, but it came at a great cost that is not well known to many who visit the park today. Understanding the story of the mountain settlements, Appalachian culture, and its legacy is a crucial part of our national history. Completing the digitization of condemnation records in all eight counties will give a greater voice to this story and a means to access it.

To access the now-fully-digitized Rappahannock and Rockingham County condemnation records:

- Go to James Madison University’s webpage, Exploring Rockingham’s Past at omeka.lib.jmu.edu/erp

- Click on “Browse Digital Collections.”

Records are organized into three categories: Court Proceedings, Muniments of Title, and Miscellaneous Documents, and can be searched by surname in all categories.

PEC is raising funds to hire another someone like Debbie Keyser—with a personal passion for this project and its history—to digitize condemnation records in Madison County. To support this effort in any way, contact Kristie Kendall at kkendall@pecva.org or 540-347-2334 ext. 7061.

This article was written by Kristie Kendall and appeared in The Piedmont Environmental Council’s Spring 2021 member newsletter, The Piedmont View. If you’d like to become a PEC member or renew your membership, please visit pecva.org/join.