A Report for The Piedmont Environmental Council

Prepared by Aaron Paul, Yale School of Forestry and Environmental Studies

November, 2011

Project Supported by: The Berkley Scholars Conservation Program & The Piedmont Environmental Council

From the Executive Summary:

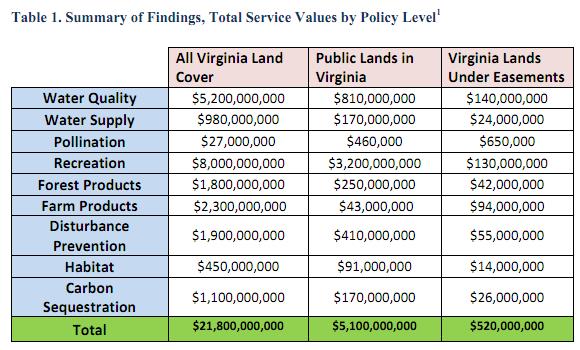

Virginia receives a myriad of economic benefits from its natural resources in the form of market products, non-market services, and added value. Using a value transfer approach, this study leverages the results of pre-existing studies to quantify the estimated annual contribution of nine such natural services – water quality, water supply, pollination, recreation, forest products, farm products, disturbance prevention, habitat, and carbon sequestration – to be approximately $21.8 billion. State and federal public lands in Virginia provide $5.1 billion of this total, and the more than 700,000 acres of private lands under conservation easement provide approximately $520 million of the total.

Over one hundred articles and policy papers were reviewed to produce per-acre value estimates for the nine different commonly studied natural benefits. These were then scaled to the desired policy levels through manipulation of the US Geological Survey’s 2002 National Land Cover Dataset.

1 Tables may not add due to rounding

With outdoor recreationists spending over $8 billion dollars within the state annually, recreation was estimated to be the single largest natural benefit to the Virginia economy. The state’s numerous forests and wetlands provide

approximately $5.2 billion in annual savings from runoff prevention, filtration, and cost avoidance. Farms and forests produce over $4 billion worth of products annually, excluding secondary processing within the state. The coastal barrier islands and beaches help coastal municipalities and property owners avoid $1.9 billion in costs stemming from with maritime erosion and storm damage. Coastal wetlands provide habitat and nurseries, used by the Chesapeake’s crabbers and fishermen, which are valued at $450 million.

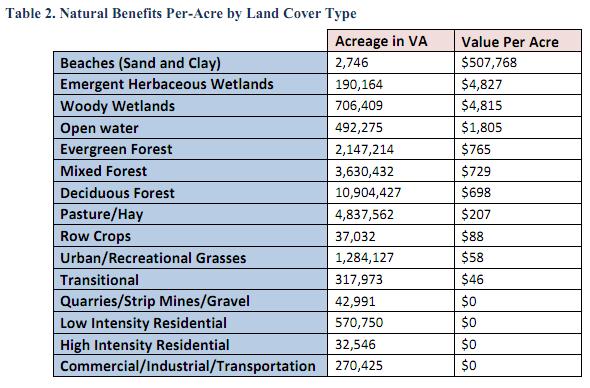

Similarly, Virginia’s farmers, vintners, and fruit growers receive $27 million in pollination services from native insects and birds. Forests, wetlands and lakes store and help supply, moderate and clean the state’s drinking water supply, valued at $980 million. Finally, the state’s forests, and, to a much lesser degree, grasslands and croplands, sequester 42.9 million tons of CO2 equivalent, which carries a $1.1 billion value based on a price of $25 per ton. The per-acre estimates used to produce the policy level values are given in Table 2.

On a per acre basis, the most valuable land cover type was sand and clay as it encompasses the Commonwealth’s relatively limited beaches. As these both defend against ocean erosion and host a tourism industry that draws over a billion dollars in annual revenue, they are the most valuable land cover type. However, merely by virtue of comprising 42.8 percent of the state’s land area, deciduous forests provide the most benefit overall. As has been widely determined in environmental economic literature, wetlands are extremely valuable on a

per acre basis as well due to the water supply, water filtration, habitat, and storm surge protection that they provide. All intensely developed, impermeable surface land cover types were estimated to provide zero natural benefits. Although urban green spaces exist and are extremely valuable, significantly more so than similar sites in rural areas, their benefit is not accounted for in the developed land cover classes. Instead the forest and grass cover types capture the benefits of parks, playing fields, and green ways.

These estimates for natural benefits include both market values for goods such as forest and farm products as well as non-market benefits such as water filtration, that save municipalities money or generate wealth but which are not evaluated in traditional accounting schemes. This report has given preference to studies that rely on cost of replacement, defensive expenditure, voluntary market, or hedonic analytical methods over those that use contingent

valuation and group valuation methods. The former group of methods assesses ecosystem service values in terms of how much it would cost to replace them, savings they make for a municipal government, or value they add to a home while the latter essentially ask respondents what they would be willing to pay to protect a resource. While contingent valuation is accepted academic practice, the goal of this project has been to quantify palpable economic impacts of natural resources and not willingness to pay, which favors the first set of methods.

Virginia’s voters, businesses, trade groups, and two most recent Governors have commented on the value of the state’s natural resources in different terms. Economic value may not necessarily be the first concern among outdoors appreciators, but it is significant. This report represents the first attempt to quantify the annual contribution of these assets to Virginia’s economy in the hopes that policy makers and business owners may better account for them in the planning for the next phase of economic prosperity within the Old Dominion.